Capt William Reeve (RGR) is a study of extremes.

On the one hand there is a British Army officer from an Army family, a graduate of Welbeck College and Sandhurst, progressing through the ranks.

On the other there is the sportsman, denied the opportunity to shine in his early teens by a bone condition and who instead had to create and capitalise on good fortune to become a regular in the red shirt and a Kenyan 7s and XVs international.

An hour’s conversation barely scratches the surface of Capt Reeve’s storied career both in uniform and on the rugby field, but there is still more than enough to fill a week of after-dinner speaking engagements.

Born in 1992, under normal circumstances Capt Reeve would have been within a rugby club’s Academy system by the time he was in his mid-teens, developing his game understanding and under the guidance of the expert practitioners who help prepare a young player for a potential life in the professional ranks.

However this was stymied by Osgood-Schlatter disease, which sees bones, muscles and tendons growing at different rates and causes pain and swelling below the knee area over the shin bone.

It is not surprising that this would have a significant impact on the adolescent future Capt Reeve.

“I couldn’t run for a couple of years,” he says. “I sat on the sidelines of every sports pitch and watched my friends develop physically and tactically, and when I got back on the horse at 15, 16, I was years behind.

“This meant my options for scholarships or Academy rugby were not available to me, and this made my decision to go to Welbeck very easy. I went there as a keen sportsman and picked up rugby there, and the routine of physically developing, training three times a week and playing on Saturday, gave me a solid two years of development which allowed me to go to university and playing at a decent level.

“But from 16 to 18, and maybe even after that, I was playing catch-up.”

Understandably frustrating it might have been, but in retrospect Osgood-Schlatter disease may have been the best thing to have happened to Capt Reeve. While the cream does rise to the top within club Academies the percentage of hundreds of talented young players who come into the system but then make it into the professional ranks is extremely small.

So instead Capt Reeve headed to Loughborough, the country’s leading sporting university, and as well as representing that institution his red shirt progressing was starting, too.

“I was lucky enough to play Corps level for the Royal Engineers and age group Service level and Combined Service level, and one season as an Army Sevens player while I was at university,” Capt Reeve says. “I then went to Sandhurst and while I joined a regiment which was going to best serve me as a soldier I was able to use my connections from age group rugby to get me back into a red jersey.

“I got on the calling notice for an Army ‘A’ fixture and then progressed through the Army ‘A’s into the Army Seniors as well as playing Army Sevens. I was fortunate that I didn’t have to work from scratch because the Battalion didn’t play rugby and the Infantry struggles as a Corps team.”

So far, so straightforward, but in June 2018 came a move which would bring more experiences than would have been initially considered.

Over to Capt Reeve to tell the story.

“My wife is from California and is happy to go around the world with me, so when a job in Kenya came up I put it down as my number one option on my PPP. My father is from Kenya and my family were over the moon, but I took it on the chin that it was going to stop me playing so much rugby. I was happy that the location and being an adjutant was good enough for my career and my life that I would take the reduction of rugby on the chin, although I was planning on coming back once or twice to play some Army rugby.

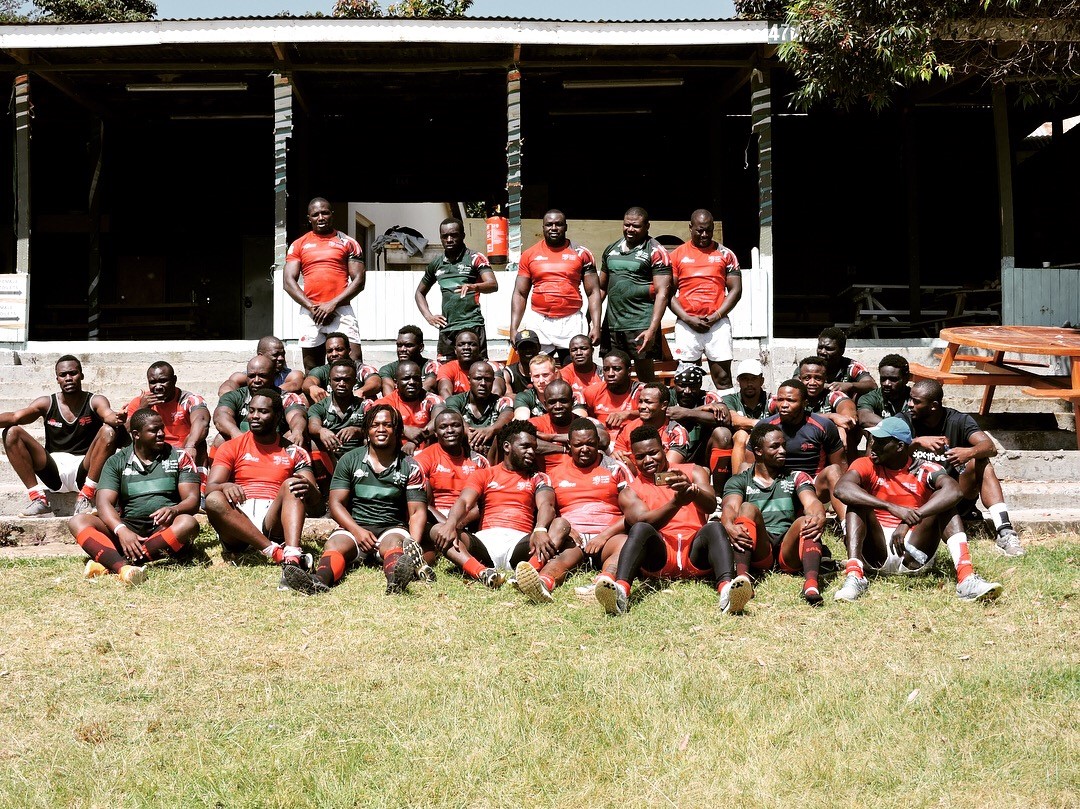

“I get to Nanyuki in the June and the PT Corps bloke who runs the gym finds out that I’m a rugby player and tells me that we’re going to be hosting the Kenya rugby team and that [team manager] Wangila Simiyu is the contact. I introduced myself to Wangila, tell him that I’m an experienced rugby player and that my father was born in Nairobi, which made me eligible to play for the team.

“I asked him if there was any way that I could be involved in the weekend at BATUK and he said ‘yes, absolutely’ and that as we were doing him a favour he could do the same for me. So I got stuck in with their fitness and team building on the Saturday, and then on the Sunday throwing the ball around on one of the pitches.

“Their coaches liked the look of me and told me that I needed to join a local club and send them some of my previous footage. Jonathan Fowke did the second bit for me, but joining the club was more difficult because there’s no centre of population in Nanyuki. So I had to get a club in Nairobi, and worked remotely from there three days a week, then back up to work in Nanyuki on a Monday and a Friday and travel to Nairobi to play on a Saturday.”

In Nairobi Capt Reeve joined Kenya Harlequins, with the first fixture coming against Impala Saracens. With the national team selectors in attendance for one of the key derbies within Kenyan rugby Capt Reeve took home both the man of the match award and an invitation to join the next national training camp.

At that point Kenya was still in the running for the repechage to qualify as the final team for the 2019 World Cup. Coaches Ian Snook and Murray Roulston saw the potential, by late October Capt Reeve was in the travelling squad and a month later he had four caps to his name following matches against Romania in Bucharest and the round-robin repechage with Canada, Germany and Hong Kong.

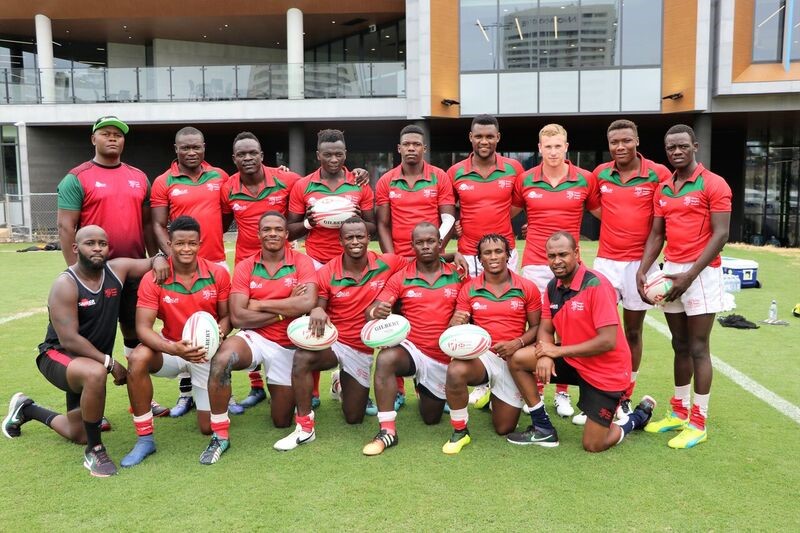

The experience having whetted his appetite for the international stage, Capt Reeve was soon on the phone to the Kenyan Sevens coaches for a similar discussion.

“They had already sent their squad to Cape Town and Dubai for the first couple of rounds,” he says. “I then got some good fortune because the Kenya Rugby Union hadn’t been able to pay all the wages. A few of the players went on a mini-strike, which forced the coaches to bring some players through from underneath and they took a gamble, liked what they saw in training and took me to Sydney and New Zealand.”

Unfortunately, while eligible under World Rugby criteria thanks to his father’s birthplace, Capt Reeve didn’t meet the Olympic criteria of needing to hold a passport for the nation he wanted to represent, and with Kenya still trying to qualify for the Tokyo Games that, as is said, was that.

“It was a quick flash in the pan, four or five caps in both codes and a good story!

“I’ve got all my stash, but the irritating thing is that my debut jersey was kept by the Kenya Rugby Union. Unfortunately the KRU struggles with funding so they have to make the most of reusing their stuff, and that meant that the kit we used at the repechage was kept as the following year’s training kit. So I don’t have a Kenya playing shirt! But it is what it is.”

Almost more important than the memories of the time on the field were the life lessons which were taken from the whole experience.

“The fundamental message I had to keep telling myself was how fortunate I was,” he recalls. “I was playing rugby with these people who played rugby to feed their family. I was playing rugby for a jolly. In a weird way I was benefitting even more so from being away from work to enjoy sport.

“But these players have to put dinner on the table – and often don’t put dinner on the table – through sport. And the amateur nature of Kenyan rugby was mind-boggling. We were training at six in the morning because guys had to be at work at 8:30, we didn’t have warm water or running water in toilets. It was the home ground for everything, and at one stage we didn’t have a lawnmower and grass 18 inches long. And from that we were being asked to beat Fiji, South Africa and New Zealand!

“It reinforced to me what these guys go through and what they do and their genuine passion for the sport, but that also for them it’s more about putting food on the table rather than winning or losing. It is unbelievably humbling.”

There were also plenty of positives to be taken back into his professional life in uniform.

“The BATUK commander and deputy commander at the time, Col Nick Wood and Lt Col Nick Andrew were very supportive. Nick Wood understood people and understood the value in having me so deeply engrained in Kenyan culture that he recognised the benefits, flying the BATUK flag in Nairobi and with PR. He held me to account on my output and trusted me to be able to do that.

“As a ‘tracksuit officer’ you have to do exactly the same amount of work as normal and make up the time which you take out for sport.

“The Army had also taught me the importance of clear and accurate communication. That was never so important as when I was trying to communicate across such a strong language barrier. I’d built up those skills being a Ghurkha officer, then to a lesser extent with a Fijian-heavy rugby set-up in the Army, and when you combine this with the work we also do about dealing with pressure it provides you as a rugby player with a whole host of transferrable skills.

“Little things like talking with my previous OC, [now-Lt Col] James Cartwright, who was also SO2 Tac Ops when I was at BATUK, so we worked in parallel for almost six years. He was fascinated and asked me about what happened in rugby and how we keep peoples’ attention focused at half-time and so on.

“It was interesting to see his thoughts on learning and developing soldiers as someone responsible for delivering the exercise and assessment of the exercise, and how we were doing that on the sports field.

“James Cartwright would also say that you can only focus on one thing. So is it the tackle area, defensive line speed, running from depth? You have to focus on one of those things.

“It is exactly the same in the Army. My job after being a platoon commander was delivering in-service training to Ghurkha soldiers. After a platoon attack I couldn’t brief the stand-in platoon commander on the 30 things they needed to do. They would write them down and then forget them all.

“The classic proverb is about chasing two rabbits and both will escape. You have to narrow it down to one thing; I’d learned that in the Army and tried to ingrain it in any team that I’m part of. Coaches might come in and say that the tackling is poor, the line speed is slow, the passing is weak, the lineout’s rubbish – you’ll forget it all. But if the coach comes in and says that in defence we need to be up quicker and in attack we need to run from deeper then everyone will remember that and you’ll be more likely to see it in the second half.”

None of this would have happened had it not been for plenty of support on the home front, either.

“I took my wife out to Kenya and then disappeared for 30-40 percent of the time,” Capt Reeve says. “It was difficult but she was totally and unconditionally supportive. She said to me that this was my boyhood dream, that I would never have the chance to do it again and that I should do it. She also came to Marseille to watch the games as well.”

Mrs Reeve also played host to the rest of the family who came out to visit for a fortnight, only to have William head to the World Rugby Sevens Series on the same day they arrived!

© Alligin Photography

Capt Reeve also had regular sojourns to join up with the Army Sevens squads throughout his two years in Kenya, including winning the 2018 Rugby Town Sevens in Denver and reaching the final of the Oktoberfest Sevens in 2019.

By the time of the latter he was a Sevens international, which is still a bittersweet memory.

“My time on the World Sevens was so brief and it was a rollercoaster. It was my boyhood dream and my debut was against South Africa! I played the worst rugby game of my life and it was heartbreaking because I knew there was so much more to offer. It was really tough for me following that weekend in New Zealand, I got injured against Scotland and was then 13th man in Sydney, meaning that I didn’t play at all.

“There’s a part of me that is devastated that I haven’t righted that wrong. I’m disappointed that the legacy I might have left might be one of my poorest performances on a rugby field.

“But the one thing that sticks out – and it’s difficult for me – was that I was used heavily in the kick off receipt. We received the kick off from South Africa. It went over the pod that was in front of me, I was right next to the touchline and watching the ball. The guy inside of me shouted that the ball was going off the field. I don’t compete for it, Pretorius jumps, plays the ball infield, South Africa catch the ball and score the try.

“That was the moment of the weekend and played across all of the social media channels! It was utterly embarrassing and looked like I was an amateur on the professional field. Even today, nearly two years on, I see it while I’m scrolling through Instagram.

“If there’s one thing that I learned from the Sevens Series it’s not so much about the rugby, it is more about the pressures of the professional game, the scrutiny that people come under and the flak they get. You’re out there, everyone is watching and it can go one of two ways.”

Fortunately the banter coming back into the Army fold was not as brutal as might have been expected. In fact, it was the opposite.

“When I then came back to the Army 7s and the first tournament after that, the coach, Isoa Damudamu, asked the rest of the team to put their hands together for my World Sevens debut. That was nice, and the pain almost – almost! – dripped away. To be considered even towards the league of the other Army rugby players who have played international rugby is humbling.”

An Ironman in summer 2021 means that Capt Reeve’s focus for the time being is on preparing for those athletic demands, but there is still a burning ambition within oval ball sports.

“Ultimately the one thing I want to achieve, and is the one thing I haven’t achieved, is running out on game day for Army Navy. In 2016 I was the 24th man in the squad, so that’s my drive and focus, and would be the cherry on top.”

Words © Chris Wearmouth

Army Rugby Union 7s image © Alligin Photography

All other images supplied by Captain William Reeve